Weathering Mental Health

Predicting the weather used to be the domain of astrologists and mystics. They looked to the stars and to lore to make forecasts. While this method was unreliable, it would take millenia before a scientific alternative emerged.

In the 1600s weather prediction started to get scientific. New tools like the thermometer and the barometer enabled the measurement of weather, and observatories were built. These weather observatories initially operated independently, only considering measurements from a single location. To make useful forecasts, measurement efforts would need to be scaled up.

The invention of the telegraph in the 1830s meant weather observatories could be networked together. Doing so vastly scaled the available data and made reliable prediction possible. Combine this network with some smart meteorologists, and in 1861 the first modern weather forecast was made:

More importantly, this same technology allowed for storm warnings. This advancement has saved countless lives. Our modern ability to model and prepare for extreme weather is a direct result of this progression.

Forecasting symptoms

Like bad weather, many mental health conditions are intermittent with long periods of stability punctuated by intense symptom episodes, but we don't currently have reliable ways of predicting these episodes. Instead, we give patients non-targeted medication (with many side effects), just in case, like telling someone to wear a raincoat 24/7, even when there are no clouds in the sky.

How do we make mental health predictable? If we use the same model as weather forecasting, mental health forecasting would need:

- Extensive measurements (weather observatories)

- Data processing (meteorologists)

- Communication (published forecasts, storm warnings)

We need progress on all three of these fronts, but any good forecasting starts with measurement. What is the equivalent of the thermometer in mental health? How can we gauge someone's mental “temperature”?

Many key mental health symptoms can only be measured by asking a patient to self-report. Today we most often measure these symptoms with iPad surveys in the doctor's waiting room or in quick conversations with a clinician. The current state of mental health measurement feels like weather prediction in the 1600s: we are collecting some quantitative measurements, but we haven't figured out how to do it at scale.

Designing a mental health monitor

To explore how we could scale up these symptom surveys, let's focus on a single, common symptom: mood.

To precisely measure this, I could ask “what is your current mood (1-7)?” But this only measures the present moment. To gather more data I might ask you “how was your mood over the previous two weeks?” But now this is a measurement of your memory of your mood, and human memory isn't very accurate. To effectively track your mood over time, I would need to survey you repeatedly.

In this way, mental health measurement is costly - it requires the patient's effort. We can't fully eliminate this cost, but we could design a solution that lowers it enough to make long-term mood monitoring viable.

Maintaining an Even Mind

Over the past four years I've been working on software to accurately measure mental health. The result is Even Mind, the first consumer-grade tool for measuring mood and energy. It takes your “temperature” at two random times a day and enables patients to see changes over time.

And it works! Users love Even Mind and some have recorded continuously for years. It can have a profoundly positive impact if you're managing a mood disorder. We can't predict these symptom episodes yet, but we can detect them.

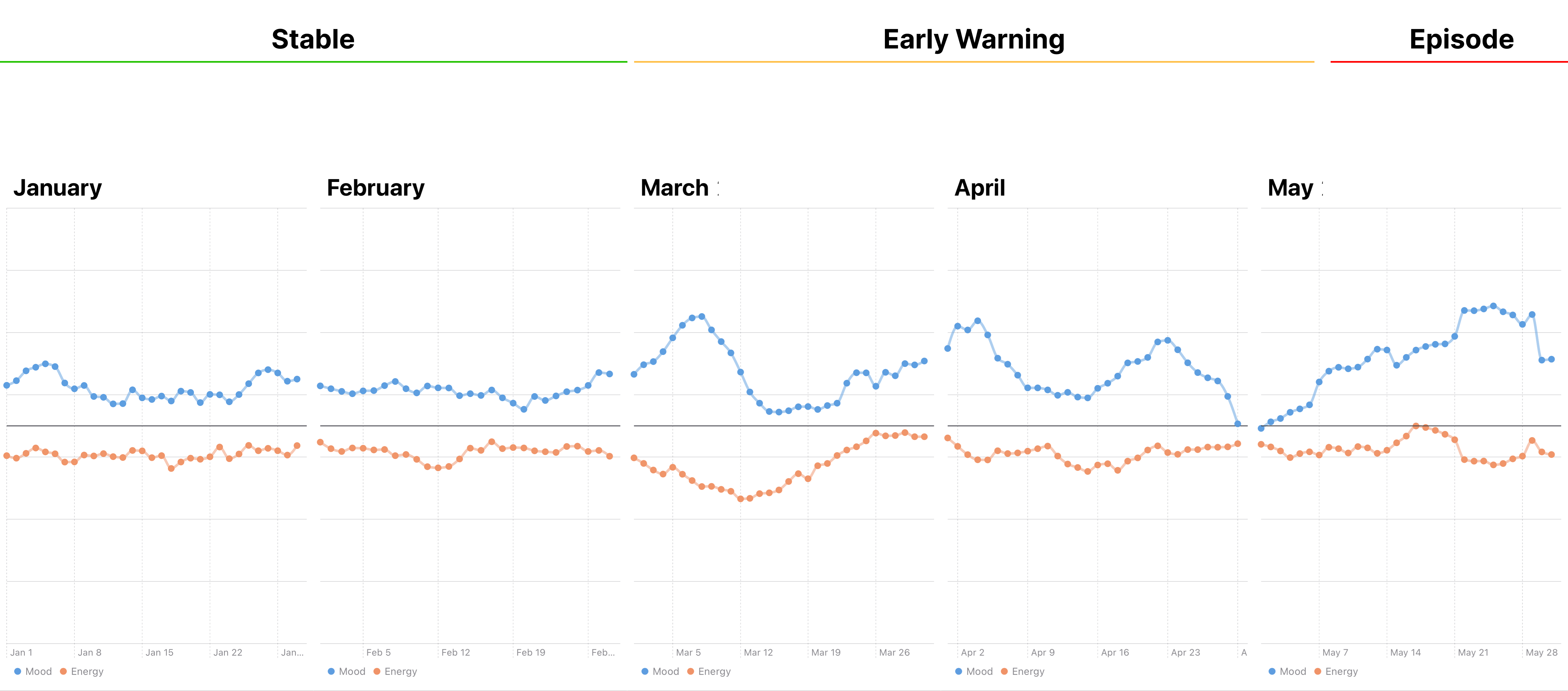

Below is what a symptom episode looks like in Even Mind for a bipolar patient. Depicted is two months of stable mood and energy followed by two months of increasing variability and then ultimately a mood episode (called mania) at the end of May. This individual didn't initially think that anything was wrong at the time, but Even Mind disagreed, and it allowed the patient to recognize this change.

Seven-day rolling average of measured mood (in blue) and energy (in orange).

Seven-day rolling average of measured mood (in blue) and energy (in orange).

Teaching the robots

My hope is that one day mental health care is responsibly automated. The role of AI is increasing and to make these tools useful, they will need to be powered by the right data. Human behavior is, and will continue to be, easy to measure. But we must balance this with data on how we feel: our moods and our energy levels for example.

To me, mental health encompasses much more than the emerging concept of “behavioral health.” I don't want a future where everyone simply “behaves correctly” but one where we can all be, and feel, healthy. I believe we can get there and mental health forecasting can help.

Thank you to my friends and family for reviewing earlier versions of this post.